|

2008 In the Media A: Retirement a labor of love for Photo Center’s ArgyrosBy Wendy Liberatore Published December 22, 2008

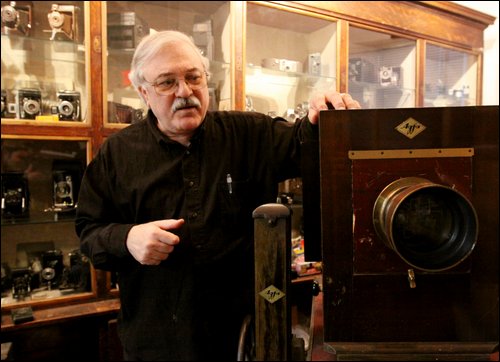

TROY — Three years ago, Nick Argyros withdrew his retirement savings to serve his lifelong avocation — photography. With the money for his golden years, the former state Department of Education researcher and statistician bought, cleaned and renovated a rundown building on River Street in Troy. He then reopened it as the Photography Center of the Capital District, a one-stop sanctuary for all things photographic. “My retirement was short-lived,” said the Loudonville resident with a laugh. The center, directed by Katherine Wright, is meant to serve photography and photographers in several ways. It provides an exhibition gallery, a museum of historic camera equipment, workstations for photographers in need of scanners, printers and computers, a center for learning with a massive library of photography books and regular schedule of workshops, and a gathering place with monthly dinners and salons. And its three floors have space left over for a fully equipped studio, where photographers who don’t have enough room or the equipment, can photograph their favorite studio subjects. If that was not enough, the center’s door opens to a camera store where used equipment along with prints and cards by local photographers are on sale. Of course, the center’s biggest draw is its nine exhibitions a year. Currently, Ken Ragsdale’s eerie and imaginative landscapes haunt the center’s clean, white walls. Q: Why did you open the center? A: I felt the Capital District deserved to have a center for photography and photographers. I’ve seen a lot of galleries come and go. There was a program, Art in Public Places, that included photography that has been cut down. So exhibition was one element. Another element, I saw this as an investment opportunity. I saw this as a real estate investment. It was an investment in the future. I bought this building outright. The third motivation was to remove the clutter in my house. I had to move my old cameras and photography books out of the house because I ran out of room and wanted to keep growing my collection. We have a substantial collection of cameras, spanning the whole history of photography. The earliest camera we have is from 1870. And we have images as early as 1840. So the three elements came together. Initially, it was going to be a little gallery and a little store. Eventually, it stretched to the whole building. Q: Is photography a tough sell? A: It’s probably harder to sell a photograph than a painting. There is a public perception that a lot more goes into a painting than a photograph. The market for art and art photography is very limited. There are various ways to decorate one’s home. Not everybody wants an $800, $1,000 photograph. That’s why art galleries have to be publicly supported. We don’t take any public monies. We want to be supported by members, but we need to double our membership. Q: How do you decide who you want to show at the gallery? A: We have a once-a-year members show and we have several group shows that are open competitions. Like, coming up in the fall of ’09, we’ll add to the Hudson River celebration with a show. People will submit their Hudson River photos and we’ll pick. For the one-person shows, like Ken Ragsdale’s, Katy [Wright] and I have to agree that the photographer has a substantial body of work and a seriousness of purpose, that they photograph something that we don’t normally get to see or do. It’s not the usual beautiful roses in the garden type of picture. Q: Why do you feel it is important to include a museum with antique cameras and photographs? A: The look of the photograph very much depends on the material, camera design and technological aspects. Most artists reject that. They don’t think it matters what camera they use. I don’t agree with that. The camera and technology of the era influences the photographer’s ability to make pictures and how the images are going to look. We just came through a major revolution with digital. During the 1800s, we went through various revolutions, when photography changed very quickly. I want the museum to show that. Q: You will exhibit these daguerreotypes, Polaroids, etc.? A: Yes, when the museum is ready for prime time. And we hope to develop a catalog with curators and historians. The catalog will identify the significant cameras over the years, like the first underwater camera, the first camera with a shutter speed of 1/4,000 of a second. Q: Do you ever feel that you should have been a photographer instead of a research coordinator for the Department of Education? A: Oh no, I loved that work. I was a math teacher first. Math was always fascinating and enjoyable. It’s a matter of exercising the left side and the right side of the brain. Everything Is IlluminatedThe Work of Ken RagsdaleBy Meisha Rosenberg

Photography Center of the Capital District, Troy, through Dec. 30 Published December 18, 2008 Ken Ragsdale will tell you that he is an artist concerned with the passage of time, and that’s true—his photographs convey the flat monumentality of childhood memories. But his work is also invested with particularly American longings and fears about life on the road. In this series, he remembers childhood camping trips along the Lewis and Clark trail. Like a memorable movie image by Antonioni or a photograph by Frank Gohlke, each image uses lighting and careful staging to create a palpable tension between objects in the landscape and the viewer’s expectations. His work is complex, despite the repetition of images, and worth getting to know. Ragsdale, born in 1962, grew up moving frequently, from Walla Walla, Wash., to northern Idaho, and he captures both the era and the Pacific Northwest region. Especially his photographs of campgrounds — Clarkston, Wallula, Arlington (all works, 2008) — reminded me of my childhood in the 1970s. Perhaps it’s because of the precisely realized Ford Econoline van circa 1961 that appears in several images. However, most scenes generalize to a universally American atmosphere of dislocation and unreality, that feeling that we’re all actors on a cardboard stage. Wishram is a good example of this: in it, a trailer drives away from the viewer down a winding highway into a tired but cheerful yellow light. It could be anywhere and any time in America where there are roads and inchoate longings. He places what he calls “monsters” in his photographs: a barn on stilts and menacing, outsized objects suggestive of grain silos or water towers that look like they mated with scalpels and funnels. These surreal landmarks enhance the eeriness that comes from blank paper props and colored gel-enhanced lighting. The most astonishing thing is that, unlike Gregory Crewdson and David Levinthal, who also photograph artificial scenes, Ragsdale makes all his own detailed architectural props from single pieces of white paper that he folds without using glue or tape. He meticulously draws and cuts out shapes with tabs, and in the final versions, the dotted lines from his drawing phase are visible. Because drawing is an important aspect of his work, some photos are framed with images of drawings. Bushes shows the infinitesimally small lines he drew for branches, and it’s not as compelling as the finished photos, but it’s still interesting. He told me, “I wanted this process of thinking, sketching, making drawings, cutting out, folding, setting up, taking photos, as this idea that at each stage it’s just based on the last stage and it’s constantly changing.” At the Photography Center, viewers are treated to the actual set he photographed for this series, mounted on a table. Director Katherine Wright delightedly pointed out that the paper barn has doors that slide open, and the tractor wheels turn. It’s a rare and generous look at an artist’s methods. Growing up he made shop drawings for his engineer father, and he continued drafting at the Pacific Northwest College of Art as a shop tech and as an assistant to sculptor William Moore in Portland. His process didn’t really come together until when he was at grad school at SUNY. He was painting when his teachers recommended he create scenes, which he then photographed, and these images took on a life of their own. Images such as The Campsite at Night, showing a Jeep and van outside a barn lit brightly from above, would fit in nicely at the current show Reality Check: Truth and Illusion in Contemporary Photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art alongside works by Crewdson and Levinthal. His work also has similarities with Gohlke and other practitioners of New Topographics—photographers who mined an uneasy relationship to industrial scenery and who came together with a show at the George Eastman House in 1975. It’s the America of lost dreams and sinister kidnappings lurking just outside the frame of the picture, where a picnic table has been overturned and a trash barrel rolls on the ground, buffeted by an unseen wind. In Wallula, the Ford Econoline and a barn radiate with alien light. One can see the outline of every branch of tree and bushes, and we can see the emptiness inside the van. Ragsdale explained, “When you see the final image you’re never really confused as to what it is. It’s paper. It’s folded paper. But when it’s constructed and photographed you know immediately that it’s also something else.” His unpopulated scenes suggest ambiguous narratives: why did the barrels fall over? Where are the cars going? His life-sized paper station wagon hanging above an escalator in Concourse B at the Albany airport, The Quest, is one of my favorite items there, because it so perfectly suggests the anonymity and narrative possibilities of travel. A teacher at the College of Saint Rose and RPI, Ragsdale will also have work as part of a group show at the Amrose Sable Gallery this month. But if you’ve never been to the Photo Center, make it a point to visit. It’s a wonderful resource. Ragsdale’s photos are an example of the kind of cutting-edge work the center aims to inspire. |

||||||